Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

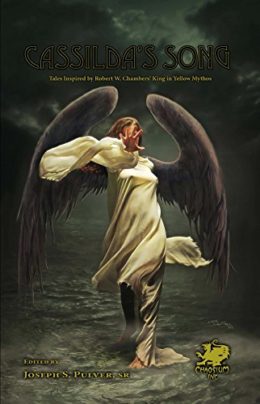

Today we’re looking at S.P. Miskowski’s “Strange is the Night,” first published in 2015 in Joseph S. Pulver’s Cassilda’s Song anthology. Spoilers ahead.

“A growl of thunder overhead and Pierce imagined the ceiling cracking open, his oblong, cumbersome body drawn upward, sucked out of his ergonomic chair into the ebony sky.”

Summary

It’s a dark and stormy night in Seattle, and Pierce is hard at work tapping out the two thousand words of his weekly theater review. In the paper’s warehouse office, only editor Hurley has a door to close. Everyone else packs into cubicles, making interoffice pranks only too easy. Someone’s just played one on Pierce, filling his screen with the headshot of a young actress he’s recently savaged. She visited his cramped apartment with pictures of her theatrical troupe, dressed in a gossamer gown and, no really, fairy wings: another artistic aspirant with more self-delusion than talent. Molly Mundy smelled of honey and lemon zest, constantly munching lemon drops. Pierce is glad he didn’t accept the one she offered from her chubby, moist hand, especially after her response to his doctored wine and groping assault was to vomit yellow goo on his hardwood floor.

Well, he got her back by going to her performance and pinning her with the perfect descriptor: porcine. Hey, it’s not as if he hasn’t persevered through plenty of knocks himself, from a father who taught him to respond to bullying by toughening up, to losing a Berkeley teaching assistantship because oversensitive fools didn’t like the language in his thesis. But he spent six years in Daddy’s (luxurious) basement, writing plays far better than the hackneyed attempts of his contemporaries, yet going unproduced. Daddy finally kicked him out, and now he gets to be the critic, defender of artistic standards and scourge of hungry poseurs!

Pierce’s theater-hating editor likes his approach, and the snark sells ads. Or so Pierce tells Ali Franco, the paper’s addled spiritualist, when she castigates him for his harsh approach. Of course she’s the one who put Mundy’s picture on his desktop. Pierce should encourage young artists, not tear them down. If he can’t do that, he should resign and follow his heart, finish his own plays, he’s forty-six years old, yet he writes like a middle-schooler with a grudge, blah blah blah. Fortunately their editor has confided to Pierce that he’ll fire Ali soon. Pierce only wishes he could fire the old hag himself.

Pierce usually tosses weird promotional material, but today he’s gotten an intriguing invitation sealed with saffron wax. The wax bears a weird hieroglyph, probably the Tattered Performance Group’s logo. He decides to attend their play, Strange is the Night. He recognizes the line from Chambers’ King in Yellow mythos, which everyone is adapting these days. It should be fun to teach Tattered a lesson…

On the way he stops at a coffee shop, where Ali Franco sits crying. What, has editor Hurley fired her without letting Pierce watch? She rushes past, eyes averted. Irritated to have missed Ali’s dismissal, Pierce heads for the Tattered Group’s warehouse stage. The cashier gives Pierce a complimentary glass of wine, which is surprisingly good. The plush lobby carpet’s gross, though, a “dense mush” of gold that seems to suck down his feet. And there are only two others in the lobby, older women with matching “C” brooches. They’re arguing about whether one must identify with the protagonist to care about a play. Pierce edges into a nearly-empty auditorium with a bare stage. His program, marked with that funky hieroglyph from the invitation, lists no cast or director.

The house lights go down. Amber illumination descends from the flies, along with a spill of orange-yellow petals. Pierce mutters “Marmalade,” his tongue oddly clumsy. His eyes roll. He finds himself face down in something resin-sticky, burned with the heat of a hundred lamps, pin-prickles in his legs. Someone’s pouring hot liquid on his backside. “That’s enough honey,” someone says. “Turn him over. Let him see.”

Pierce sees pale yellow light arcing over him–his own vomit. A suspended mirror shows his honey-smeared nakedness, strewn with petals, trembling. In his mind he composes his review, but the words sink into the cheap paper and disappear.

Fat fingers dig into his shoulders, deep enough for the nails to scrape bone. Somewhere in the wings, Molly Mundy waits in her gossamer gown: giggling, patient, hungry.

What’s Cyclopean: Everyone in this story has one word that can destroy them, whether “porcine” or “fired.” Meanwhile Pierce’s boss thinks himself quite the wordsmith for editing “in short” to “in brief.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Pierce has strong opinions about all sorts of people, but reserves his chief contempt for people who think they might get somewhere in life. “Porcine” women with any sort of ambition are particularly contemptible. “Illiterate bloggers” also come in for derision.

Mythos Making: The titular play, Strange is the Night, includes a number of quotes from The King in Yellow—or at least its publicity materials do.

Libronomicon: Alfred Jarry was the rage when Pierce was in school. (Best-known play: Ubu Roi or The King.) Now everyone is doing stage adaptations of some dude named Robert Chambers.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Pierce would, in fact, benefit from some therapy.

Anne’s Commentary

Ah ha ha ha. Here is one of my guilty pleasure microgenres, the CRITIC who gets his COMEUPPANCE. I definitely have a love-hate relationship with critics and criticism—a good review of my own work, with insightful comments, will make my day, and week, and a good chunk of my aeon; a bad review can ruin all of the above. Well, maybe not the aeon-chunk. I enjoy a great review I agree with and can have an ecstatic rant over one that pans a favorite. But best of all may be a truly radioactive panning of something I hate, liberally sprinkled with snark.

And wow, have the number and variety of commentators grown in this the Internet Era. Was there not an innocent time when only the elite few critics held forth to large audiences, first via newspapers and magazines, then via TV and radio? The rest of us had to squee or carp en famille, or around the water cooler, or at most in mimeographed zines of dubious legibility. Or, like Howard and Friends, in snail mail missives.

Those were the days of my two favorite fictional critics, George Sanders’ cobra-sleek Addison DeWitt in All About Eve and the insignificant of physique but powerful of (poison) pen Ellsworth Toohey of The Fountainhead. They dwarf poor Pierce in range of influence and self-awareness, but Pierce has venom as potent as theirs, just not the fangs to administer it efficiently. He has to choose weak prey, all those tragically hopeful/hopeless amateurs and ingenues. Only their hides are tender enough for his weak jaws to clamp onto, his tiny teeth to gnaw the death-dose in. Or rather, Pierce likes to think he delivers death-doses, yes, and with a single razor-honed word. Like porcine. I figure most of his targets survive his reviews, their dreams succumbing not to his quill but to the more pressing imperatives to pay rent and buy food more sustaining than instant ramen noodles.

I don’t know. Maybe he shoots Molly Mundy dead with that porcine he’s so proud of. Maybe not — she’s still giggling at the story’s end, or he imagines she is. Pierce wanted to shoot her dead, though. Her and every impractical dreamer who reminds him of his distant father and unappreciative professors, of fellow students who got the plaudits and positions he craved, of the theatrical world that rejects his plays, over and over, preferring what is clearly inferior, because not by Pierce. He even got his theater critic job because the reigning critic quit and couldn’t find anyone else hungry enough to take her place. Ego-wound after ego-wound, which make his ego grow not sturdier but sicklier, inflamed with envy, feverish with stymied ambition. Swollen, fit to pop.

Nope, Pierce can’t do, and he’s too mean to teach, so he criticizes in the spirit of a self-avenging angel. I could kind of pity him if that was all he did, but he also exploits the young women who come to him for a boost. It’s strongly implied that he slips Molly a date-rape drug. It’s stated outright that he glories in dismissing any ingenue desperate enough to sleep with him. Get out. Go. Caesar dismissing a thick-ankled dancing girl after first rolling his eyes over her performance and then copping a feel.

That he does worse than write nasty reviews is necessary to justify the end he comes to. Still, I semi-agree with “Cam’s” companion in the theater lobby who argues that fiction can’t have emotional impact if no one identifies with the protagonist. I was semi-identifying with Pierce’s frustration until he spiked Molly’s drink. After that, I was done with him and more concerned for Ali Franco, a rather Trelawney-like sibyl, warning Pierce to mend his sophomorically vindictive fuming before it’s too late.

The “Cam” mentioned above is short, no doubt, for Camilla. I’ll bet her friend, also wearing the diamante initial “C,” is Cassilda herself. Other references to the Chambers mythos are blatant, such as the saffron hieroglyph—Yellow Sign!—that Pierce receives, and the bits of Cassilda’s Song he vaguely remembers: “twin suns sink beneath the lake,” “strange is the night,” “Song of my soul, my voice is dead.” Others are subtler, like the peppering of yellow throughout: Molly’s lemon drops, crumbled saffron wax stuck in a keyboard, the bile-yellow of vomit, a glass of Pinot Grigio, jonquil-scented powder, whiffed urine, a gold carpet.

That carpet! Curious how our last tale of a wronged woman’s revenge also featured floor covering like carnivorous foot-sucking vegetation. Does this figure forth some sort of male terror of pubic hair or the placenta? Or just of gross rugs?

Sometimes my mind goes where no blogger’s has gone before, for good reason.

Chambers-esque is the closing, whisking us from the dingy reality of Pierce’s world for a true theater of the weird, perhaps a door into Carcosa. That Pinot Grigio may come straight from the Yellow King’s vineyards. It’s a more potent mindbender than veterinary sedative in cheap Chardonnay—it opens Pierce’s eyes to amber illumination, a skewing ceiling of delicate gold chains and pulleys, a shower of orange-yellow petals. And honey, sticky as resin, poured hot over his naked body, because he is suddenly naked, splayed beneath a mirror, vomiting arcs of pale yellow light. Molly’s scent, both acquired and natural, has been described as honey-sweet. In the theater of the weird, Molly waits off-stage, giggling.

I don’t think it’s really Molly, though. Whether Pierce is drugged to madness or transported to another plane, he’s obsessed her into the poster-child for all his objects of derision, all the victims of his weekly two thousand words. Had she/they deserved his critical flogging? Had he earned any right to administer it? Do desserts or rights even matter, or is selection to meet the King in tatters (gossamer) random?

All I’m sure about is you shouldn’t open any invitation bearing the Yellow Sign. Yellow envelopes might be dangerous, too.

When in doubt, recycle unread. Also, avoid one-star reviews. You never know Who the author may worship….

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Woe, woe to the blogger caught in a web of self-referential recursion as she attempts to review a story about the sudden but inevitable downfall of an un-virtuous reviewer. I shall make a noble attempt to do so without being drowned in honey or dismembered. At some point, because the advantage of a “reading” series over a “review” series is that I don’t have to stay on topic, I shall shift from trying to figure out what I think of this story to nattering on about theater.

Or maybe I’ll start there. The King in Yellow, though usually encountered in script form, is a play—meant to be performed. Meant to enthrall a director who’ll cling to their sanity long enough to run auditions, who’ll stage Cassilda’s big scene with the perfect set and lighting, who’ll keep actors from self-destruction and techies from murder all through the run. So, much like any other play. Like Shakespeare and Ibsen, it must hang on the sacrifice and passion of people throwing themselves into an imagined world, and on the audience swept up in the search for catharsis. If King takes those emotional journeys to a deadly pinacle, it’s one that follows as logically from everyday theater as the Necronomicon does from realizing, after hours immersed in a good book, that you’ve forgotten to eat.

The tragedy driving “Strange is the Night” is that you can become jaded to these wonders. And it is a tragedy, in the theatrical sense. Pierce may be a lousy human being. He may be a lousy artist, shielded by privilege and isolation from the lessons that would make his scripts sing. His sole dismal satisfaction may come from destroying (piercing) the dreams of others as his own have been destroyed. But his tragic flaw is his inability to seek anything in a play beyond its flaws—to allow himself to be pierced. At which point, making that piercing literal is the only reasonable revenge the universe can take. Actress Molly Mundy just happens to win the role of avenging fury. (Mundy = mundi = world? Or Mundy = Monday = Moon-day? Interesting name games here.)

All of which would work better for me if Pierce didn’t also showcase the same misogynist flaws as so many other doomed horror narrators. If his central failing is meant to be one of art appreciation (and if we’re playing with Chambers, that’s more than sufficient to be lethal), why does he also need to be a fat-shaming twit? Why does he need to be the sort of guy who drugs ingenues to get laid, and then throws them out when they puke? Don’t get me wrong, I’m not against smothering that kind of guy in honey and/or feeding him to elder gods. But so much of horror comes down to a dance-off between punishing women for sexual agency versus punishing men for being misogynist predators… and there must be more original ways to get yourself a starring role in a deadly performance. Right?

But then there are the two ladies discussing kabuki and unsympathetic protagonists: “One identifies with a mask, a stereotype, if tradition prepares us for it.” There’s certainly plenty of tradition preparing us for Pierce’s stereotype.

At first, I wanted a deeper connection between Pierce’s final curtain call and Chambers’s masterpiece. The references seem omnipresent but tenuous—a quote here, a mask there—unless there’s a honey-drowning scene beside the Lake of Haldi that I missed. But the more I think about it, the more Carcosa makes the story hang together. It’s no coincidence that the curtain’s rise is the first time that Pierce is impressed by anything. Perhaps The King in Yellow is the play that comes to you—with whatever force necessary—when all other theater has lost its ability to make an impression. Molly Mundy may be getting her hungry revenge, but she’s also making art. Whether it’s good art… well, we’d have to ask a reviewer.

Next week, in Brian Hodge’s “The Same Deep Waters as You,” some bright minds decide that an animal whisperer is just the person to get in touch with the Deep Ones. You can find it in many anthologies including Lovecraft’s Monsters.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” is now available from Macmillan’s Tor.com imprint. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.